The Problem of Short-termism

Achieving sustainable development is hard. Climate change, environmental degradation, and resource scarcity are calling for it, but short-term interests always seem to trump long-term considerations. Despite our best efforts to inform, stimulate, regulate, and govern, individuals tend to prefer immediate payoffs over greater future benefits, companies and shareholders want fast returns on investments, and governments need to show results to their populations quickly.

A common thread in our struggles to make development more sustainable is underlying competitive pressures that lead to short-termism, i.e., structures from which agency cannot seem to escape consistently or only under certain conditions, despite our best governance efforts.

Unfortunately, with tensions among great powers increasing, sustainable development is likely to face its most problematic challenge yet. Great power rivalry, on a finite planet without a world government, offers a fierce competition from which there is no escape. It represents a struggle for survival that will fundamentally influence what countries prioritize and where countries cannot sacrifice the short term for the long term.

Sustainable Development

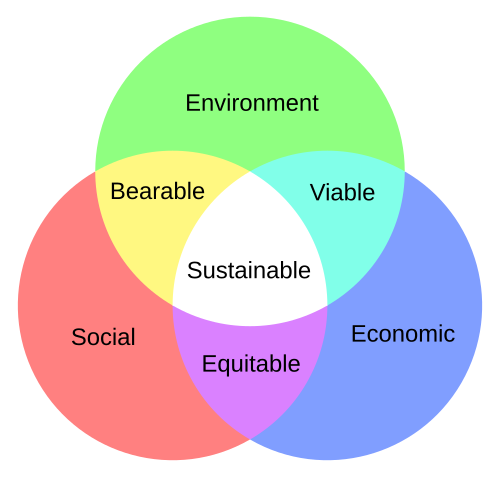

Sustainable development is generally defined as "development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs" (WCED 1987, 8, i.e., the Brundtland report). It centers around finding a balance between environmental, economic, and societal considerations, its three dimensions (see figure 1), both in an inter- and intragenerational context. The aim is economic growth that is environmentally bearable and socially acceptable, which relates it to but also sets it apart from notions of degrowth.

Achieving sustainable development has proven difficult. While technical and behavioral solutions exist and we generally know what needs to be done to achieve a circular economy, less waste and pollution, and better resource management, challenges are pervasive. Think of all the education campaigns, transparency measures, CO2 pricing, market regulation, cultural and behavioral nudges, agreements by broad coalitions, and global governance efforts. They can reap local successes, but the global picture remains unchanged: we are overstepping planetary boundaries left and right, and social issues abound. While we can identify many incidental causes for each of our sustainability (policy) failures or lack of commitment, e.g., lobbying, disinformation, or government flip-flopping, we can also discern that human psychology and underlying competitive pressures are structural causes that lead to problematic short-termism in the absence of enforceable means of governance.

Humans have an evolutionary psychological predisposition for satisfying our needs in the here and now, i.e., a tendency to prioritize the immediate over the long term. We wish to thrive and not just survive. That is not to say we cannot think long-term. Whether we set aside harvest for the winter or save up for our pensions, humans clearly make deliberate decisions between cravings and savings. It only becomes problematic when there is pressure applied, which brings us to the next point.

We are also continuously in competition. Individuals for jobs, partners, wealth, influence, or whatever status symbols. If they fail to meet immediate expectations, important opportunities may be lost. Businesses in the market fight for market share, with stakeholders and competitors incentivizing them to prioritize short-term profits over company longevity. If sustainability measures diminish their competitiveness or turnover, then choices have to be made. Politicians, whether in democracies or not, think about popular approval and favor policies and projects that have tangible results soon, rather than a better result ten years later when their successor is in office. In short, in settings with strong competitive incentives, we prioritize the immediate, for otherwise we won't make it to the next round. Of course, cultural factors mediate just how this competition plays out, and we may have institutional safeguards in place, but our desire to thrive instead of merely survive will always keep part of this competition alive.

It is in the wake of competitive pressures and our desire to thrive that long-term concerns are lost. To correct this, governments set regulations such that our behavior need not facilitate overconsumption, limit pollution, and provide a fair division of wealth, however defined. Regulations and standards can force longer-term thinking in individuals and companies, information campaigns can help understand the necessity and shape a culture of considering the long-term in our daily actions, and governments can cement important long-term goals in cross-party agreements, international arrangements, and even constitutions if need be. The harder laws and agreements are to change, the longer they are likely to last. None of these means are perfect, of course, but institutions to make and enforce agreements can be set in place.

Great Power Rivalry

Contemporary global politics is shaped by increasing great power rivalry between the US, China, the EU, Russia, and a host of other countries. The world has moved from a unipolar one led by the US to a militarily bipolar one and an economically multipolar one. The global system is starting to look like Europe before WWI, but instead of nation-states in a European setting, we now have continent-sized states on a global level. This rivalry is troublesome for sustainable development as it entails strong competitive pressures, and there is very little to govern it.

The competition between countries for wealth and power runs deep. The desire to be secure drives countries to increase their capabilities sufficiently so as to ensure their survival and way of life, only for others to do the same, creating the security dilemma we all know. This competition forces countries to focus on short-term economic growth and military readiness. For if one does not, one may be dominated or conquered and not survive in the long term. This is different from economic rivalry, where competition may lead to the necessary innovations in green tech. Instead, it emphasizes economic and resource nationalism and avoiding supply chain dependencies. While 'anarchy is what states make of it', realists are quick to point out that history has yet to show we can truly move away from this situation. While periods of stability have occurred, periods of increasing tensions and war have as well. It also does not help that we are facing increasing rivalry in a time of climate change and resource scarcity, putting pressure on this competition.

Great power rivalry also lacks global governance institutions to mediate it. The global system is anarchic, without a world government. International agreements and their enforcement require the world's powerful countries to be aligned. In times of rivalry, there is no credible means of enforcement, as there is no one with a preponderance of power. Reputational damage, economic sanctions, and political isolation still exist, of course, as means by some countries to 'punish' others, making it harder for them to make transactions. As such, countries tend to play by the commonly accepted norms and rules, as they benefit from doing so. But when national interests are at stake, and these can be defined incredibly broadly, they will do what is necessary to face the immediate threat, taking resources away from sustainable development and towards military or other industrial ends. Whereas governance can help handle short-termism within countries if populations are willing and between countries if relations are friendly, the competition between countries undermines any global governance effort.

It is unfortunate that the world is facing its most difficult challenges in terms of climate change, environmental degradation, and resource scarcity in a time of increasing great power rivalry. As we may expect, efforts of sustainable development to wax and wane in tandem with the tidal wave of great power rivalry, humanity faces with a profound conundrum: how to temper great power rivalry and make progress on sustainable development, i.e., how to overcome the harder edges of the security dilemma while we don't have years to establish trust, transparency, or governance?

So what now?

Looking at the challenge of great power rivalry, it seems that lasting sustainable development will require a full rethink of humanity's nature and organization, focused on global cooperation instead of competition. This is, of course, as utopian as it sounds. Still, international troubles should not lead to despair. We should simply accept them and look elsewhere for possibilities. First, countries that are not drawn into this great power rivalry or whose security and development are not significantly affected by it may be a first place to look when starting global efforts to coordinate towards sustainable development. Second, we may hope that the technological optimists are right and we innovate our way out of environmental problems, though this may still leave the social dimension unattended. It may also be limited by the formation of trade blocs along rivalry lines. Third, we may re-emphasize national efforts where there is enough popular backing or pressure. Whether by governments, through regulation or education, or by citizens, through initiatives or consumer choices, the sharpest edges of problematic competition can be softened.

In addition, we need to face the deeper question of how to handle pervasive competition and the resulting short-termism, focusing less on incidental governance failures or lobbying and more on the structures behind it, if we want to have lasting efforts towards sustainable development. How can we incorporate a certain realism concerning political feasibility into sustainable development thinking? How to create institutional structures that facilitate long-term commitment while accepting human nature and the inevitability of competition on a finite planet? Otherwise, all solutions will be there in theory, while we will ecologically crash, possibly not even learning from our mistakes then, rather than jointly managing climate change, environmental degradation, and resource scarcity in times of great power rivalry.

Dr. Daniel Scholten, PhD, is a lecturer at Wageningen University and Research in the Netherlands.

Check out our other work, the geopolitics of the global energy demand shift.